By Graham Healy

Prior to 1987 when the Federation of Irish Cyclists was formed, the governance of the sport on the island was very much divided with a number of different bodies representing cyclists.

In the 1930s and 40s, the sport was governed by the National Cycling Association (NCA), an all-Ireland organisation. However, in 1947 the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), decreed that the NCA should confine its area of jurisdiction to the 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland.

This didn’t sit well with the NCA and they were subsequently expelled from the UCI after refusing to agree with their decision.

Two years later, a number of cycling clubs broke away from the NCA to form Cumann Rothaiochta na hÉireann (CRE) which would just have jurisdiction in the Republic. To complicate matters further, another body was formed to represent clubs in Northern Ireland.

The Northern Ireland Cycling Federation (NICF) received official recognition from the UCI and became part of the British Cycling Federation.

Over the years, there were a number of high-profile clashes between the two main bodies – the NCA and CRE. At the World Championships in Frascati in 1955, a team representing the NCA tried to take part in the race. A scuffle broke out between the NCA team and the official team from the CRE and a number of NCA members were arrested by Italian police.

The following year in Melbourne, a team representing the NCA once again tried to take part in the Olympic Road Race and sixteen years after Melbourne, there was yet another incident involving an NCA team trying to take part in the Olympic Road Race.

The Olympics that year were being held in Munich and four riders were selected to represent Ireland in the road race – Liam Horner, Noel Teggart, Kieron McQuaid and Peter Doyle.

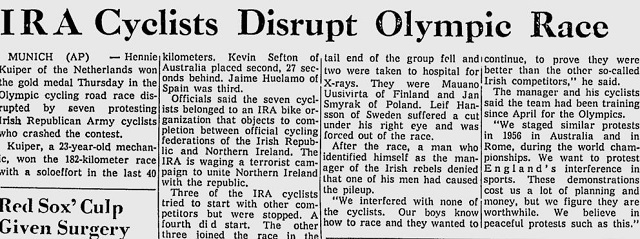

The NCA decided that they would use the Games as an opportunity to stage another protest, so seven riders from the organisation decided to try to take part in the race.

The riders were apparently protesting at the inclusion of Teggart from Banbridge in Northern Ireland on the team and they lined up at the start with leaflets filling their jersey pockets which explained their protest. German police did spot three of them before the race started and they were removed from the starting line.

However, one rider – Pat Healy – did manage to start undetected with three others jumping in soon after the race started after hiding in a wood. The other three included the winner of that year’s Rás Tailteann – John Mangan and another Kerryman Batty Flynn.

In those opening kilometres, Flynn actually led the race for a time. The Kerryman had no number and this caused some confusion for the TV commentators who described him as “an unknown Dutchman.”

The race was to get a little more heated shortly afterwards though when the Irish riders clashed. According to newspaper reports afterwards: “German motorcycle police promptly snatched them off their bikes – but not before one was involved in a 15-bike pileup.”

“Irish Olympic officials said the IRA cyclist caused the pileup in an attempt to knock Irish Olympian Noel Teggart out of the race.”

The NCA rider involved was Mangan. There were words between the pair which ended up with Mangan grabbing Teggart’s handlebars. The NCA rider pushed him to the side of the road where he held him for a couple of minutes.

“An NCA rider came alongside me and grabbed the handlebars of my machine, forcing me off the road,” Teggart told reporters afterwards. “He continued to hold my bicycle for perhaps two minutes and by the time I got free the rest of the field were out of sight.”

“By the time I got mounted again, the rest of the field were out of sight. This was my last competitive race and I desperately wanted to do well. I am disgusted by the whole affair. Before this I had a certain amount of respect for the NCA but not any longer.”

Teggart wasn’t the only person who was disgusted by the incident as Taoiseach Jack Lynch was also in Munich that day. “These team representatives were cycling for Ireland and the interference was a travesty of sportsmanship — reflecting no credit on the country,” he stated.

The NCA representatives had a different view of the incident though.

“We interfered with none of the cyclists,” a spokesman for the NCA team told reporters afterwards. “Our boys know how to race and they wanted to continue, to prove they were better than the other so-called Irish competitors.”

“We staged similar protests in 1956 in Australia and in Rome, during the world championships. We want to protest England’s interference in sports. These demonstrations cost us a lot of planning and money, but we figure they are worthwhile. We believe in protests such as this.”

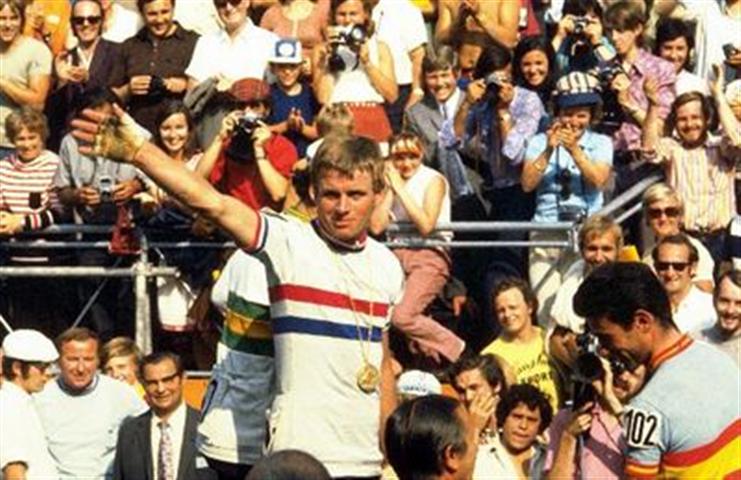

The race meanwhile was won by Dutch rider Hennie Kuiper who attacked with 40 kilometres remaining. He won ahead of Clyde Sefton of Australia with Jaime Huélamo of Spain taking the bronze medal.

The other three members of the Irish team did manage to finish the race, with Horner finishing in 38th position, McQuaid two places further back and Doyle in 69th place. All riders finished in the same time, 2’32” behind Kuiper.

In the bigger scheme of things, the incident didn’t gain too much international publicity. After all, the road race did take place just days after eleven Israeli team members were taken hostage and killed by the Palestinian group Black September.

However, it was the last serious incident between the various Irish cycling bodies and before the end of the decade, progress would be made to merge the governance of the sport on the island.

Here are some highlights from the road race in the ’72 Olympics.

My dad was at that ! Liam Horner was in his club

Margaret Mahony

Wow that is amazing!