By Graham Healy

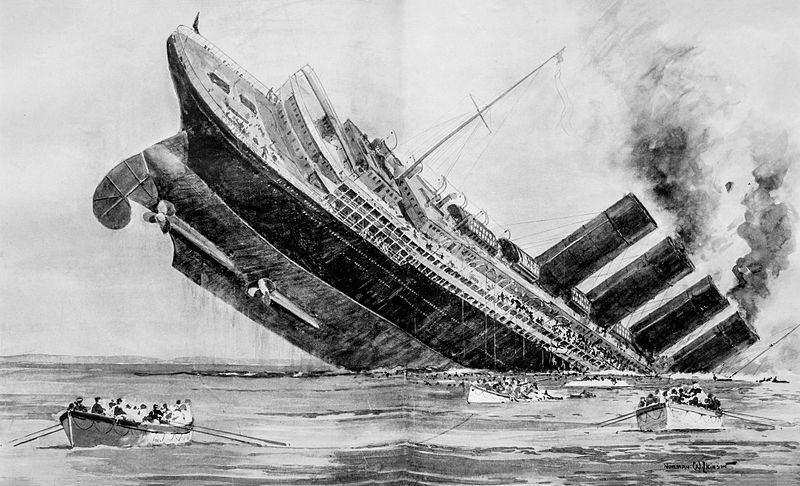

In 1915, the RMS Lusitania was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-20 off the Old Head of Kinsale off the south coast of Ireland. The ship sank in eighteen minutes and resulted in the deaths of 1,198 people. It was considered to be one of the contributory factors for the US entering World War One.

The Cunard liner had been sailing from New York to Liverpool and in the months prior to the sinking, the German government had declared the waters around Great Britain and Ireland to be a war zone.

Despite the threat, the Lusitania still managed to sell out its second-class tickets for the voyage and a considerable amount of first and third-class tickets. In total, 1,959 people were on board when the ship left New York.

Five days later as the ship neared the Irish coast, the captain of the Lusitania received a warning about submarine activity. On the following afternoon, the U20 surfaced and spotted a large ship coming over the horizon.

When it was 700 metres away, a torpedo was launched which hit the starboard side of the ship. There was a massive explosion and the ship started listing severely soon after. Despite there being sufficient number of lifeboats on board, only a handful were successfully lowered.

Many of those that were unable to make it into a lifeboat succumbed to the cold temperatures as it took a number of hours for help to arrive from the Cork coast. Of the 1,198 who died, only 289 bodies were recovered with most of the burials taking place in either Kinsale or Cobh.

Despite the massive death toll, 761 passengers or crew managed to survive. Amongst the fortunate ones was Ralph Mecredy – an Irish cyclist who had competed at the Stockholm Olympics in 1912.

At those Olympics, the British Olympic Association (BOA) had entered three teams in the cycling events, with one team from each of the separate English, Scottish and Irish governing bodies for the sport.

Mecredy along with Francis Guy, Michael Walker, Matthew Walsh and Bernhard Doyle were the riders to represent Ireland.

Mecredy was the son of an Irish cycling champion – R.J. Mecredy – who is credited with inventing the sport of bicycle polo and it was while he studied at Trinity College in Dublin that the younger Mecredy came to prominence as a cyclist.

Amongst his feats were to become the first man to cover 300 miles unpaced in one day on the road in Ireland, and he also held the Irish 24 hour record.

These performances amongst others helped Mecredy get the nod for the Irish team to travel to Stockholm. Just prior to the race taking part though, a French representative protested against the determination of the Cycling Committee to allow England, Ireland and Scotland to compete as separate nations. However, the Olympic cycling committee stood by its decision and the three countries were allowed to race.

The riders lined up in an individual time trial starting at 2am on the 7th of July which counted towards both the individual medals and the team medals. The riders faced a mammoth 315-journey with the competitors going off at two minute intervals. 123 took part in the race and Mecredy finished in 80th place, in a time just over 13 hours.

Rudolph Lewis of South Africa won in a time of 10 hours and 42 minutes and Michael Walker was the top Irish finisher in 67th place.

Mecredy returned to Ireland after the Games and the following year, he moved to the U.S. to study medicine at the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan. It was on his return to Ireland two years later that Mecredy booked his passage on the Lusitania.

Mecredy later provided testimony regarding the sinking of the ship saying that he had been on deck when the torpedo struck and that the impact was as “though the ship was suddenly checked by a gigantic and invisible hand.” He recalled, “there was an explosion, and everything seemed to turn black. Huge spouts of water, apparently black, came up all around us, and then washed down over the decks.”

As the ship was sinking, Mecredy decided that jumping from the stern was the better option and managed to obtain a life jacket before jumping.

After sliding down a rope into the sea, Mecredy swam for a lifeboat which was already crowded but he managed to scramble aboard. A reporter for The Cork Examiner later asked him was he invited in.

“Well,” Mecredy admitted, “to tell you the truth I was not. But I did not think it an occasion to stand upon ceremony, or rather, to swim upon ceremony.” A trawler picked up the lifeboat and took the survivors to Queenstown (Cobh).

Mecredy later became Chief Medical Officer in New Zealand before retiring in England where he died in 1968 at the age of 80.

Source: