By Graham Healy

By 1987, Irish riders had come close to the top step at the Professional Men’s Road Race at the World Championships. However, the gold was proving elusive. In 1962, Shay Elliott had finished second behind Jean Stablinski in Salo, Italy. Sean Kelly claimed the bronze medal in Goodwood, England, in 1982, and Stephen Roche did the same in Altenrhein, Switzerland, the following year.

Prior to the 1987 Worlds, Roche had claimed a remarkable double when he won both the Giro d’Italia and Tour de France. He had struggled with motivation after the Tour, and instead travelled to Villach, Austria where that year’s race was taking place with the aim of helping his teammate Kelly win the race.

Following on from the Tour, Roche took part in a number of criteriums back in Ireland. However, he crashed toward the end of the race in Cork, landing on the same knee that he had hurt two years previously. Despite the pain, he was still confident of being able to turn in a good ride at the World Championships.

The circuit seemed to be better suited to a strong sprinter like Kelly. Eddy Merckx had predicted before the race that it would be won by a sprinter, which seemed to be the common consensus.

Roche and Kelly trained with the rest of their small five-man team in the days preceding the race, and those days together helped to build the spirit that would come to the fore during the race. Paul Kimmage, Martin Earley, and Alan McCormack made up the rest of the team.

The riders woke up on the morning of the race to torrential rain, which would have suited both Kelly and Roche, as neither rode particularly well in the heat. The circuit was just twelve kilometres long, so they would have to face twenty-three laps.

Given the slippery conditions, the Irish riders stayed near the front of the bunch so as to stay out of trouble. The race was the usual war of attrition, but despite numerous riders being dropped as the laps went on, with just one circuit remaining there were still about seventy riders in the lead group.

At the start of that last lap, a number of riders went clear. Roche helped to bridge the gap with Kelly on his wheel. The new lead group contained just seven riders, including the two Irishmen. Roche put in a strong effort to pull this group clear, but others were to get across, including a number of danger men such as Canadian Steve Bauer, and the previous year’s winner, Moreno Argentin. The lead group swelled to thirteen riders, and they started to work well together.

Roche continued to do the lion’s share of the work at the front as he chased down attacks by Dane Rolf Sørensen and Dutchman Teun van Vliet. However, when he bridged across to Van Vliet, there was no sign of Kelly. The group had split, and Roche was now clear with four others.

In addition to Van Vliet and Sørensen, the group also contained Guido Winterberg of Switzerland and German Rolf Gölz. Roche was hesitant to work, looking behind for his compatriot. There were only a handful of kilometres left, though, and it didn’t look like Kelly would make it back.

Roche later described the moment in his biography, The Agony and the Ecstasy: “I looked behind and could see they were stalling. I became anxious. I wondered what was happening. How could Kelly lose contact at this stage? What I did not know was that Kelly and Argentin were having their own private battle of nerves, Kelly refusing to lead the pursuit of a breakaway group that included his teammate, Argentin refusing to lead Kelly because he feared Kelly would then beat him in the sprint.”

Coming into the finishing straight, Roche seized his chance and attacked through a narrow gap against the barriers. Winterberg hesitated for a split second to follow him through that gap and that’s all it took. He was now clear.

He described those final moments later, saying, “With about 500 metres left I took one last look behind and decided that Kelly’s group was not coming back in time and so I prepared for the attack. The remarkable thing was that there was still something in my legs and when I went I tried to use every available ounce of energy. I was turning a big gear when I attacked and just kept turning it.”

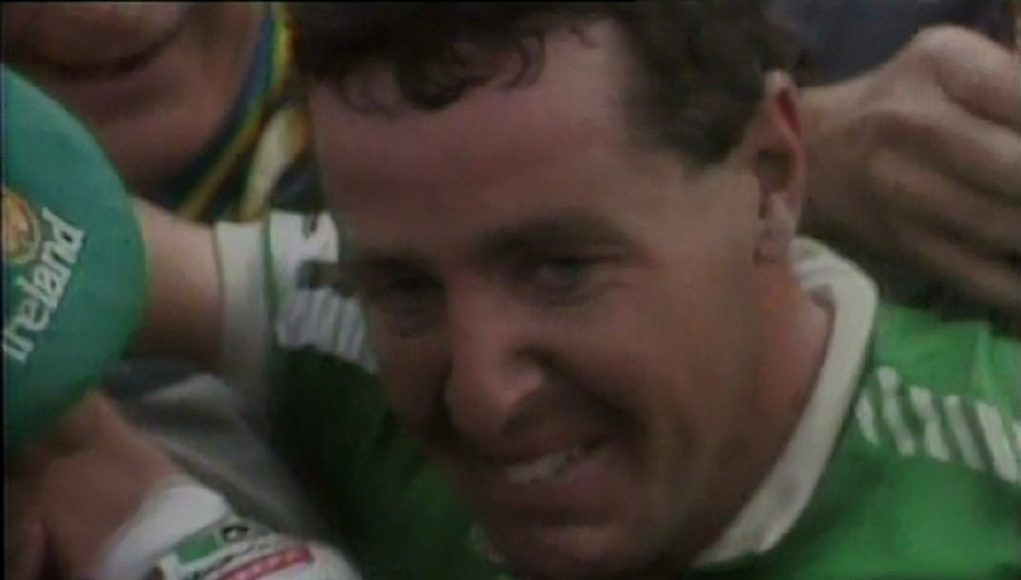

There was a rise to the finish line. The chasing group had now caught the four others, and it seemed that they might catch the slowing Roche. However, he just managed to hang on ahead of Argentin and Juan Fernández of Spain.

He said, “After about 300 metres I glanced under my arm and got the most beautiful surprise of my life. The others were well behind me and I was going to be World Champion. I kept turning my big gear but close to the line the incline got a little more severe and I struggled through the last 50 metres. But, by then, it did not matter. I was not going to be overtaken.”

The original team plan had been to set up Kelly for the win, but that didn’t matter now: Kelly was also overjoyed, throwing his hands up as he crossed the line in fifth place. Roche would reveal later on, “Even though I went to the World Championships expecting nothing, I now believe that my performance in Villach was the best single-day effort of my career. I don’t think I have ever ridden better in my life.”

The team celebrated at their hotel that night, and were joined by many of the Irish supporters who had travelled over. Kelly did come close again to winning the rainbow jersey two years later in Chambery, finishing third behind Greg LeMond. Despite being one of the best one-day riders ever, the Worlds proved elusive for Kelly and Roche’s victory remains the only Pro or Elite World Road Race title won by an Irishman.